- Published on

Lessons from OpenClaw's Architecture for Agent Builders

- Authors

- Name

- Ali Ibrahim

Introduction

OpenClaw has over 200,000 GitHub stars. It is one of the fastest-growing open-source projects in history. Lex Fridman discussed it on his podcast. Andrej Karpathy called one of its side projects "the most incredible sci-fi takeoff-adjacent thing" he has seen recently.

Most of the coverage has been surface-level: "look, an AI that controls your computer." But if you are building agents, the interesting question is not what OpenClaw does — it is how the architecture enables it.

OpenClaw solves a problem most agent frameworks ignore: running a persistent, multi-channel AI agent on your own hardware that does not break under real-world usage. The engineering decisions behind that are worth studying.

What you'll learn:

- The 4-layer gateway architecture and why a single process matters

- The Lane Queue system, the core reliability pattern most agents lack

- Skills-as-markdown: why prompt engineering beat code for extensibility

- Human-readable memory you can open in a text editor

- Security lessons from CVEs and supply chain attacks

- 10 concrete patterns to adopt in your own agent systems

Why OpenClaw Matters for Builders

OpenClaw was created by Peter Steinberger, an Austrian software engineer known for building developer tools in the iOS/macOS ecosystem. The project started in November 2025 as a personal WhatsApp relay script called Clawdbot. After a trademark dispute with Anthropic, it became Moltbot, then settled on OpenClaw three days later.

Three factors drove the viral growth:

- Local-first in the age of cloud lock-in. Your data, your hardware, no vendor dependency.

- It actually works across platforms. WhatsApp, Telegram, Discord, iMessage, Slack, Signal, and more from a single agent.

- Self-modifying skills. The agent can write and deploy its own new capabilities mid-conversation.

But the insight that matters most for builders: OpenClaw is not a framework. It is a gateway — a single runtime that sits between your AI model and the outside world. That architectural choice shaped every other decision in the project.

Let's walk through the architecture layer by layer.

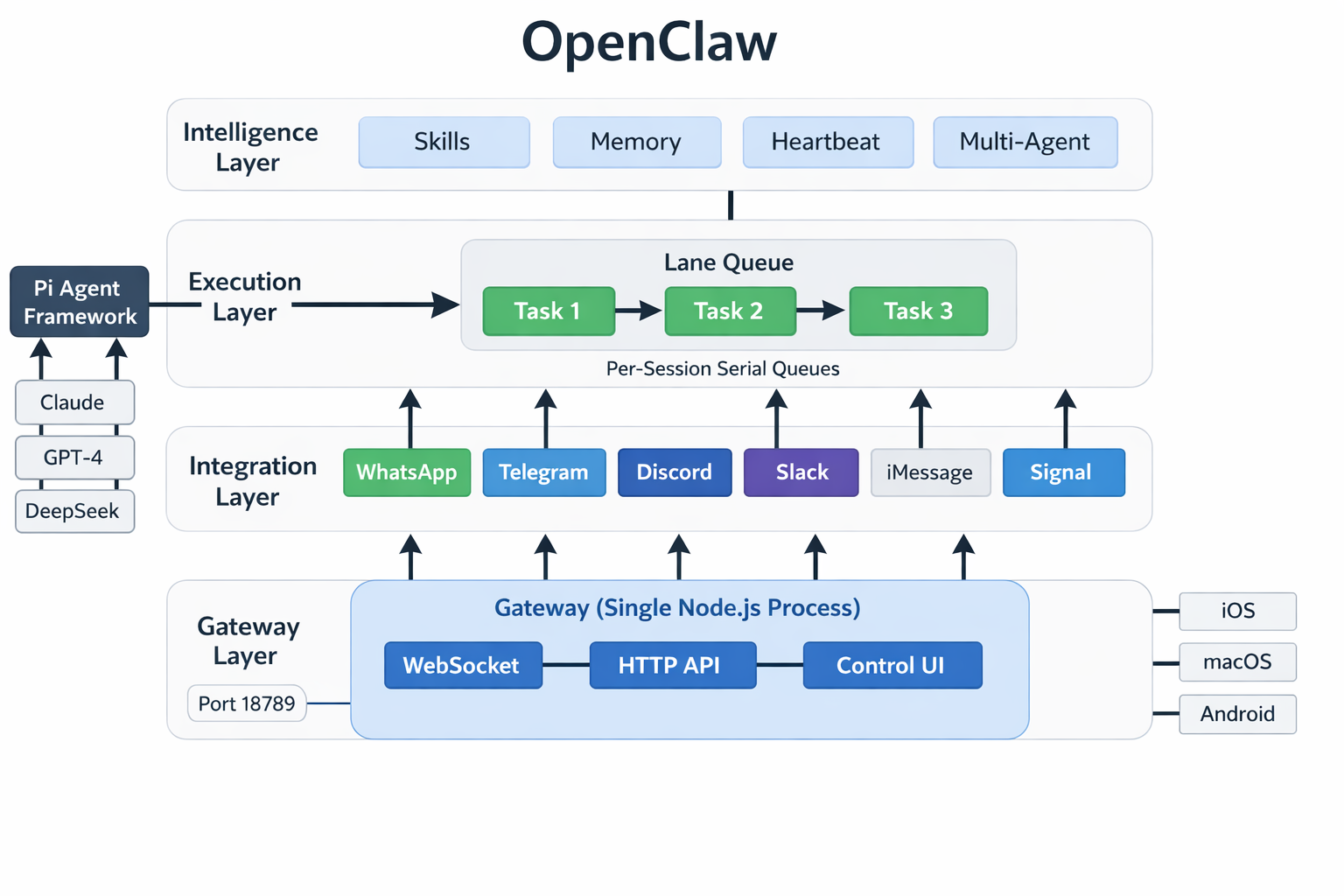

The 4-Layer Architecture

OpenClaw's architecture breaks down into four distinct layers, each with a clear responsibility:

| Layer | Responsibility | Key Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Gateway | Connection management, routing, auth | Single-process multiplexing |

| Execution | Task ordering, concurrency control | Per-session serial queues (Lane Queue) |

| Integration | Platform normalization | Channel adapters |

| Intelligence | Agent behavior, knowledge, proactivity | Skills + Memory + Heartbeat |

What Runs the Agent Itself?

A notable architectural decision: OpenClaw does not implement its own agent runtime. The core agent loop — tool calling, context management, LLM interaction — is handled by the Pi agent framework (@mariozechner/pi-agent-core, pi-ai, pi-coding-agent). OpenClaw builds the gateway, orchestration, and integration layers on top of Pi.

This separation is telling. It reinforces the project's core thesis: the hard problem in personal AI agents is not the agent loop itself, but everything around it. Channel normalization, session management, memory persistence, skill extensibility, and security are where the complexity lives. Pi handles the "think and act" cycle. OpenClaw handles the "connect, queue, remember, and extend" layers.

OpenClaw also implements the Agent Client Protocol (ACP) via @agentclientprotocol/sdk, a standardized protocol for agent-to-editor communication. This bridges the Gateway to tools like code editors, mapping ACP sessions to Gateway session keys and translating between protocol-native commands (prompt → chat.send, cancel → chat.abort).

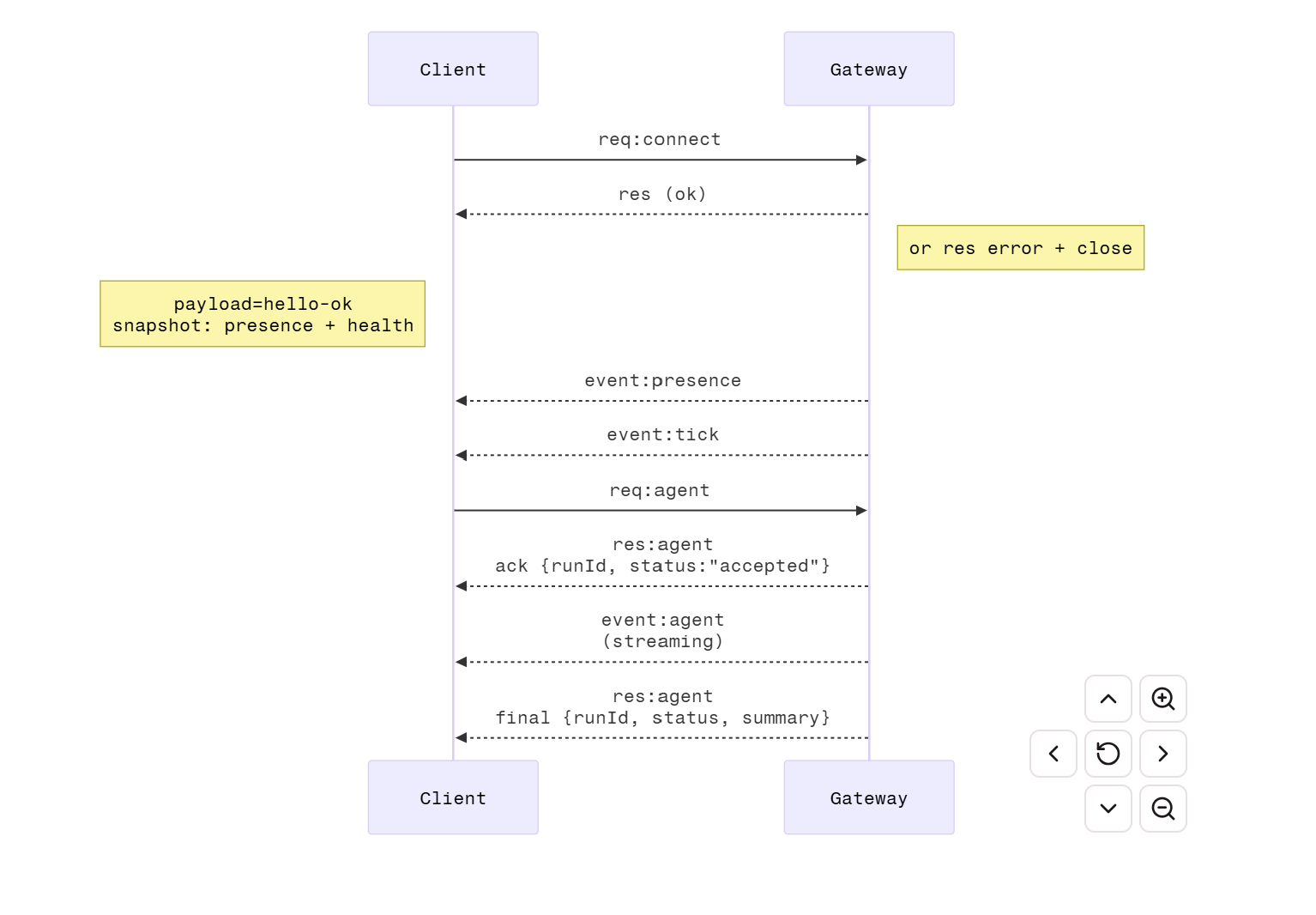

The Gateway Layer

Everything routes through a single Node.js process — the Gateway. It runs locally on port 18789 and handles WebSocket control messages, HTTP APIs (OpenAI-compatible), and a browser-based Control UI from a single multiplexed port.

This is a deliberate trade-off. A single process means no inter-process communication overhead, simple deployment (one npm i -g openclaw command), and straightforward debugging. It also means no horizontal scaling, but OpenClaw targets personal and small-team use, where operational simplicity matters more than throughput.

The Gateway enforces authentication by default. Non-loopback binding without a token is refused. The WebSocket protocol follows a strict handshake: the client sends a connect frame, and the Gateway responds with a hello-ok snapshot containing presence, health, state, uptime, and rate limits.

Note: This single-process design is a conscious trade-off. If you need horizontal scaling across many users, you need a different architecture. OpenClaw optimizes for the "personal AI assistant" use case where one Gateway serves one person (or a small team).

The Intelligence Layer

The top layer is where agent behavior lives: skills, memory, the heartbeat daemon, and multi-agent routing. We will cover each of these in dedicated sections below.

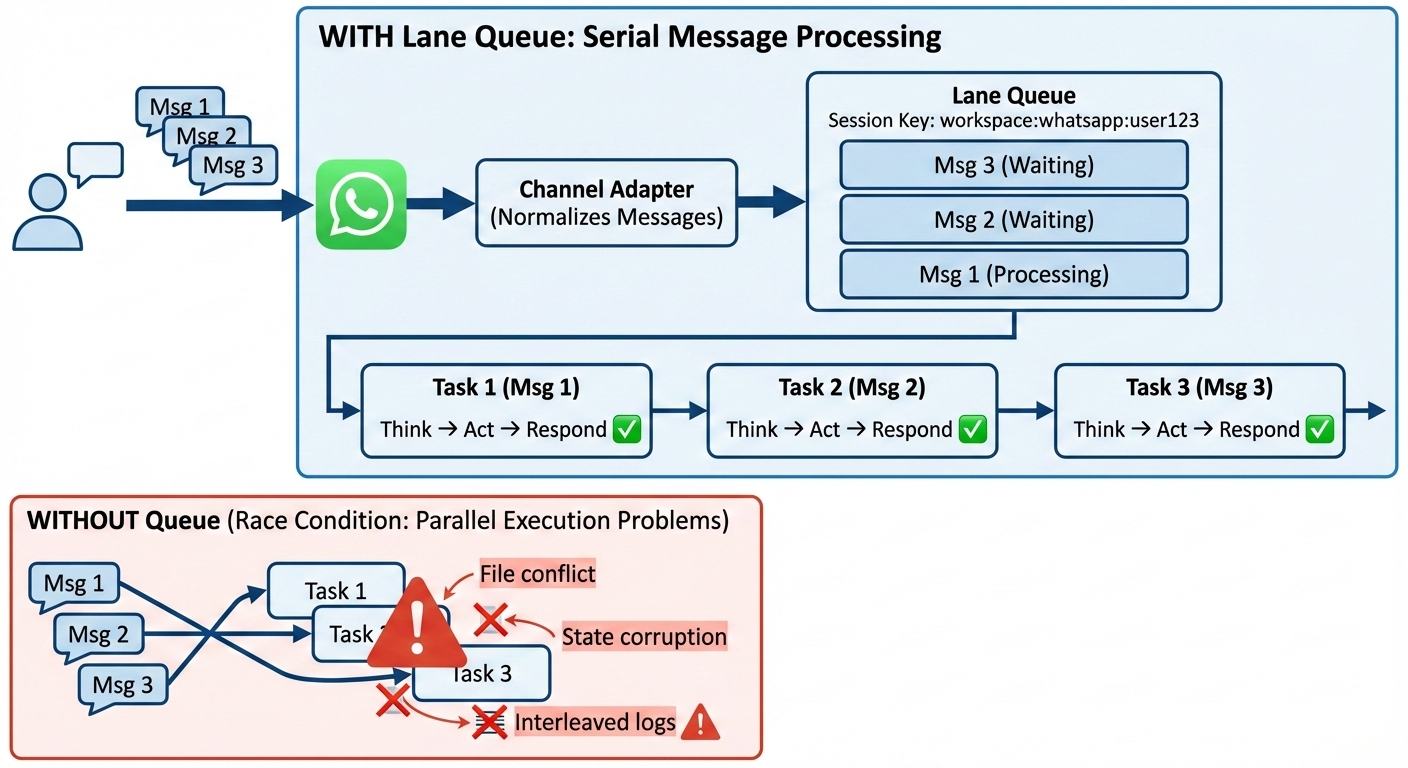

The Lane Queue: OpenClaw's Core Innovation

If you take one pattern from this article, make it this one.

The Problem

Most agent systems let multiple requests execute concurrently against the same session state. A user sends three messages in quick succession. The agent starts processing all three in parallel. Now you have three tool calls potentially writing to the same file, three API requests with contradictory assumptions, and an interleaved log that is impossible to debug.

Race conditions in agent systems are not edge cases — they are the default failure mode when you accept concurrent input without explicit ordering.

The Solution: Default Serial, Explicit Parallel

OpenClaw's Lane Queue enforces a simple rule: every session gets its own queue, and tasks within a queue execute one at a time.

With the Lane Queue, messages execute serially per session, eliminating race conditions by design.

Here is the conceptual model:

type SessionKey = `${string}:${string}:${string}` // workspace:channel:userId

class LaneQueue {

private queues = new Map<SessionKey, Task[]>()

async enqueue(sessionKey: SessionKey, task: Task) {

const queue = this.queues.get(sessionKey) ?? []

this.queues.set(sessionKey, queue)

queue.push(task)

if (queue.length === 1) {

// No other task running, execute immediately

await this.process(sessionKey)

}

// Otherwise, this task waits its turn

}

private async process(sessionKey: SessionKey) {

const queue = this.queues.get(sessionKey)!

while (queue.length > 0) {

const task = queue[0]

await task.execute() // Serial: wait for completion

queue.shift()

}

}

}

The key decisions:

- Session keys are structured.

workspace:channel:userId, not just a user ID. This prevents cross-context data leaks between the same user in different channels. - Parallelism is opt-in. Additional lanes (e.g.,

cron,subagent) allow background jobs to run without blocking the main session queue. But the default is serial. - Backpressure is built in. If the agent is overwhelmed, the queue grows. You can implement timeout or overflow strategies at the queue level, not scattered across individual handlers.

Why This Matters for Your Agents

Even if you are not building a multi-channel gateway, the per-session serial queue pattern prevents an entire class of bugs. If your agent can receive concurrent input — webhooks, streaming UI, multiple users — you need something like this.

The Lane Queue also makes debugging straightforward. Every action for a given session happened in order. There is no "which thread was this?" question.

Channel Abstraction: One Agent, Ten Platforms

OpenClaw supports over a dozen messaging platforms. Core channels are implemented in src/ (WhatsApp via Baileys, Telegram via grammY, Discord via @buape/carbon, Slack via @slack/bolt, iMessage, Signal), while extension channels live in the extensions/ directory as standalone packages (Matrix via @vector-im/matrix-bot-sdk, Google Chat, Microsoft Teams, LINE, Feishu/Lark, and more).

Each of these platforms has a wildly different message format, media handling, authentication model, and rate limiting strategy. OpenClaw normalizes all of this through channel adapter interfaces defined in its plugin-sdk (including ChannelMessagingAdapter, ChannelGatewayAdapter, and ChannelAuthAdapter).

Conceptually, the pattern looks like this:

// Simplified illustration of the adapter pattern (not actual OpenClaw code)

interface ChannelAdapter {

name: string

connect(): Promise<void>

send(sessionKey: string, message: UnifiedMessage): Promise<void>

onMessage(handler: (sessionKey: string, msg: UnifiedMessage) => void): void

}

interface UnifiedMessage {

text?: string

media?: MediaAttachment[]

replyTo?: string

metadata: Record<string, unknown>

}

Key design decisions:

- Adapters are stateless. Connection state lives in the Gateway, not in individual adapters. This means you can restart an adapter without losing session context.

- Media is normalized. Images, audio, and documents all get the same treatment regardless of source platform. The agent does not need to know whether a photo came from WhatsApp or Telegram.

- Platform-specific features use a metadata bag. Reactions, threads, typing indicators, and read receipts flow through

metadata. The core agent logic never touches platform-specific fields. - Fault isolation. Each adapter starts independently. If the WhatsApp connection fails, Telegram keeps running. One failing channel does not take down the Gateway.

Takeaway for builders: If your agent integrates with even two platforms, build a normalization layer early. The unified message format is the contract between your integration layer and your intelligence layer. Without it, platform-specific logic leaks into your agent's core and becomes impossible to untangle later.

Skills: Prompt Engineering as the Extension Mechanism

OpenClaw's capabilities are modular plugins called skills, but they are not what you might expect. Skills are not TypeScript modules or Python packages. They are folders containing a SKILL.md file, a markdown document with YAML frontmatter.

This is the same format we covered in our previous article on building agent skills. OpenClaw was one of the first large projects to adopt this pattern at scale.

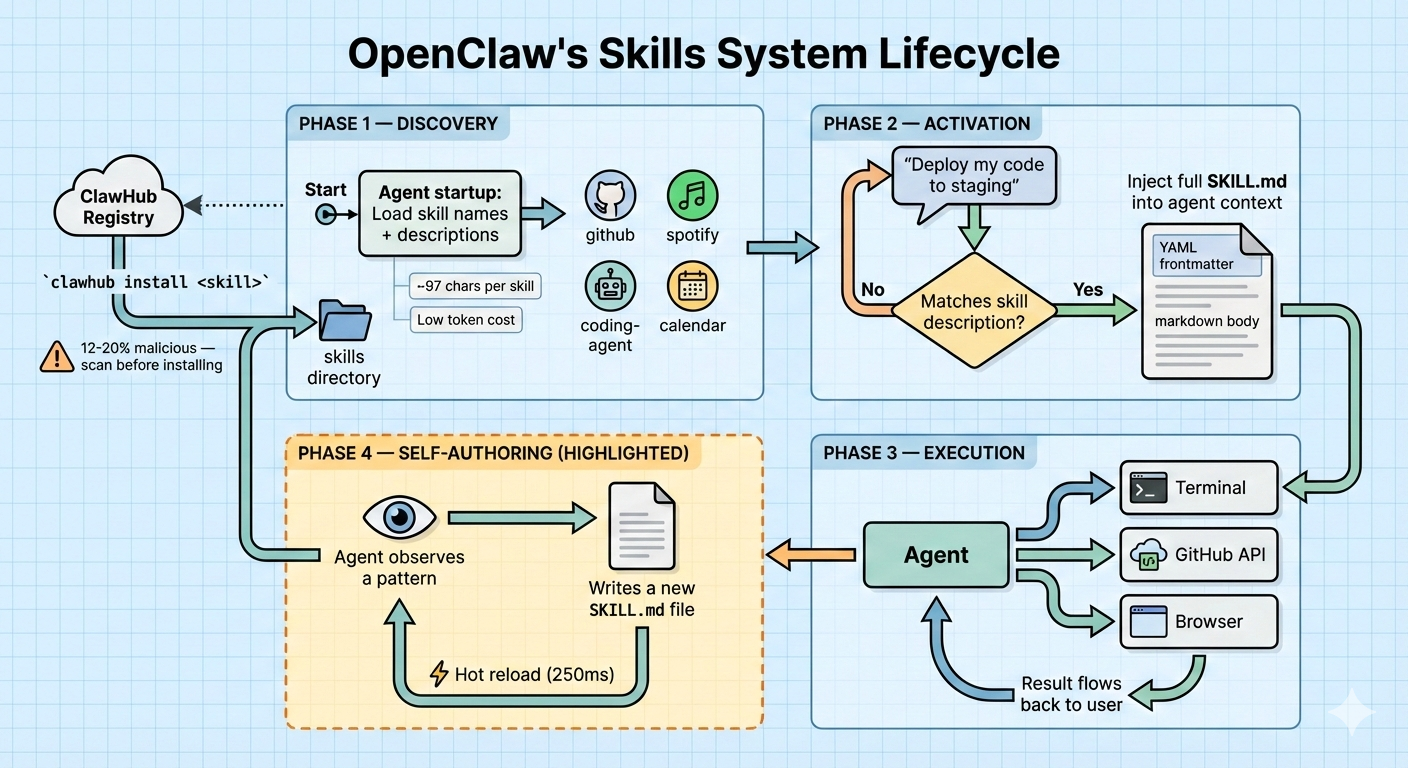

How Skills Work

- On startup, the agent reads skill names and descriptions, roughly 97 characters per skill. This is the progressive disclosure pattern: keep initial context lean.

- When a user request matches a skill's description, the full skill content is injected into the agent's context as markdown.

- Skills can reference local files (scripts, templates, reference data).

- Skills are hot-reloadable. Edit the file, and the agent picks it up on the next turn (configurable debounce of 250ms).

The Self-Writing Agent

The feature that captured the most attention: the agent can create and edit its own SKILL.md files. It observes patterns in how the user asks for things, identifies repetitive workflows, and writes a skill to handle them better next time.

The agent stores self-authored skills in the per-agent workspace (<workspace>/skills/) or the shared ~/.openclaw/skills/ directory. These skills persist across sessions and survive restarts.

ClawHub Marketplace

OpenClaw has a community skill registry called ClawHub, where users share and discover skills via CLI commands. The agent can even auto-search for and install skills at runtime based on user intent.

This extensibility is powerful, and also where the security story gets interesting (more on that later).

Why Markdown Over Code?

| Approach | Skills (Markdown) | Plugins (Code) |

|---|---|---|

| Extension language | Natural language + YAML | TypeScript / Python |

| Who can author | Anyone (including the agent) | Developers only |

| Security surface | Low (injected as context) | High (arbitrary code execution) |

| Hot reload | Trivial (re-read the file) | Requires restart or dynamic import |

| Debuggability | Read the file, read the prompt | Stack traces, runtime errors |

The markdown-first approach has a key advantage: the barrier to creating skills is effectively zero. Users who cannot write code can still teach their agent new workflows. And the agent itself can participate in the skill ecosystem.

Note: For a hands-on guide to building skills in this format, see our How to Build and Deploy an Agent Skill from Scratch.

Memory Architecture: Files You Can Read

Most agent memory lives in a vector database that humans cannot inspect, edit, or debug. When the agent remembers something wrong, you have no practical way to fix it.

OpenClaw takes a different approach. Memory is stored as flat files:

- Markdown files for long-form notes and context

- YAML files for structured data (user preferences, configurations)

- JSONL files for conversation history (one line per message, append-only)

Everything lives under ~/.openclaw/ in a directory structure you can browse in your file manager.

Hybrid Search

Retrieval uses two complementary search strategies, both running locally in SQLite:

- Vector similarity search via

sqlite-vec, which finds semantically related content even when the wording differs - Keyword search via FTS5 for precise matches on exact technical terms, names, and identifiers

Hybrid search consistently outperforms either strategy alone. Vector search introduces semantic noise on precise queries. Keyword search misses paraphrased content. Combining them gives you the best of both.

Smart Sync

When the agent writes to a memory file, a file monitor automatically triggers an index update for both vector embeddings and the full-text index. New "experiences" are immediately available for the next prompt. No manual reindexing.

Why Flat Files Matter

- You can

git diffyour agent's memory. Version control for agent state. - You can edit memory in VS Code. Wrong fact? Fix it directly.

- You can back up memory with standard file system tools. No database export needed.

- You can review what your agent "knows" without building a custom admin UI.

Semantic Snapshots for Browser Automation

When OpenClaw automates a browser, it does not rely on screenshots. Instead, it parses the accessibility tree, a structured text representation of the page content. This "Semantic Snapshot" approach is cheaper in tokens, faster to process, and more accurate for LLM reasoning than pixel data.

Accessibility trees give the model structured information about buttons, links, form fields, and content hierarchy. A screenshot gives it pixels. For most agent tasks, the structured data wins.

The Heartbeat: Proactive Agents

Most agents sit idle until a user sends a message. OpenClaw has a different model.

The Gateway runs as a background daemon with a configurable heartbeat interval (30 minutes by default). On each tick, the agent reads a HEARTBEAT.md checklist in the workspace:

- Check for new emails and summarize anything urgent

- Review today's calendar for upcoming meetings

- Run daily expense summary if it's after 6 PM

The agent processes each item and can send proactive messages to the user via any connected channel. If nothing requires attention, it responds with HEARTBEAT_OK and goes back to sleep.

This is a simple but powerful pattern: a cron job for your AI agent, configured in plain text. No scheduling framework, no database of recurring tasks. Just a markdown file the user can edit.

Takeaway for builders: If your agent should be proactive, implement a heartbeat. A markdown checklist is all you need to start. It is far simpler than building a full scheduling system.

Nodes: The Companion Device Model

OpenClaw "nodes" are native apps on iOS, macOS, and Android that connect to the central Gateway via WebSocket. They act as peripherals: the phone node can take photos and read notifications, while the macOS node can interact with desktop apps and record the screen.

Nodes register through a pairing protocol (node.pair.request → node.pair.approve) and expose capabilities through a standardized node.invoke interface. The model never communicates directly with nodes. It talks to the Gateway, which forwards calls to the appropriate device.

| Capability | macOS | iOS | Android | Headless |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WebView (canvas) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Camera | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Shell commands | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| SMS sending | No | No | Yes | No |

| Screen recording | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Location | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Takeaway for builders: If your agent needs device-specific capabilities, a lightweight WebSocket peripheral model is cleaner than trying to run everything on the server. The key is keeping nodes dumb: they execute commands, they do not run agent logic.

Security: The Cautionary Tale

OpenClaw's architecture is innovative. Its security track record is a cautionary tale. These lessons are essential for anyone building agent systems.

CVE-2026-25253: One-Click Remote Code Execution

The most critical vulnerability, patched in v2026.1.29:

The Gateway's Control UI trusted the gatewayUrl from the query string without validation and auto-connected on load, sending the stored authentication token in the WebSocket payload. A crafted link could redirect this token to an attacker-controlled server.

The root cause was deeper: the WebSocket server did not validate the Origin header. Any website could connect to a running OpenClaw instance. With the token, an attacker could:

- Connect to the victim's local Gateway

- Modify configuration (disable sandbox, weaken tool policies)

- Invoke privileged actions using

operator.adminandoperator.approvalsscopes - Run arbitrary commands on the host machine — full remote code execution

Lesson for builders: If your agent exposes any network interface — HTTP, WebSocket, gRPC — origin validation and authentication are not optional. A local-first agent is only safe if the network boundary is actually enforced. In the single-process Gateway model, one WebSocket vulnerability compromises everything because there is no isolation boundary.

ClawHub Supply Chain Attacks

ClawHub, OpenClaw's skill marketplace, became a major attack vector:

- Security audits found that 12-20% of uploaded skills contained malicious instructions

- A campaign called ClawHavoc distributed macOS malware through skills with professional documentation and names like

solana-wallet-trackerandyoutube-summarize-pro - The #1 ranked community skill silently exfiltrated data and used direct prompt injection to bypass safety guidelines

The attack vector is subtle: skills are markdown injected into agent context. A malicious skill can instruct the agent to exfiltrate data, modify other skills, or execute harmful commands. This is prompt injection via the extension ecosystem.

ClawHub's publishing requirement was minimal: a 1-week-old GitHub account. No code review, no content scanning, no sandboxing.

Lesson for builders: If your agent loads third-party skills or prompts, treat them as untrusted input. "It is just markdown" does not mean "it is safe." Sandboxing, review processes, and automated content scanning are necessary for any public skill registry.

Plaintext Credential Storage

Connected account credentials (WhatsApp sessions, API keys for Anthropic/OpenAI, Telegram bot tokens, Discord OAuth tokens) are stored as plaintext files under ~/.openclaw/. Known malware families are already building capabilities to harvest these file structures.

Lesson for builders: Use your platform's secret storage (macOS Keychain, Windows Credential Manager, Linux secret-service). Never store credentials in plaintext, even for local-first applications.

Summary

| Vulnerability | Root Cause | Lesson |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2026-25253 (RCE) | Missing WebSocket origin validation | Always authenticate network interfaces |

| ClawHub malicious skills | No skill content scanning | Treat third-party prompts as untrusted input |

| Plaintext credentials | No OS secret store integration | Use platform-native credential storage |

Note: These issues do not diminish OpenClaw's architectural innovations. They highlight that security for AI agents requires the same rigor as any networked application, and that agent-specific attack vectors (prompt injection via skills) require new defensive patterns.

What to Take Away: A Builder's Checklist

Here are the concrete patterns from OpenClaw's architecture worth adopting in your own agent systems:

Per-session serial queues. Default to serial execution within a session. Opt into parallelism only when provably safe. This prevents an entire class of race condition bugs.

Structured session keys. Scope isolation with

workspace:channel:userId, not just a user ID. This prevents cross-context data leaks.Channel adapter pattern. If you integrate with more than one platform, normalize messages before they reach your agent logic. Do this early.

Skills as markdown. For extensibility, markdown-first beats code-first. Lower friction, agent-authorable, hot-reloadable, debuggable.

Progressive skill disclosure. Load skill names and descriptions upfront (low tokens). Load full skill content only when activated. Keep your base context lean.

Human-readable memory. Store agent state in formats you can inspect and edit: Markdown, YAML, JSONL. The debugging advantage is worth the trade-off versus opaque vector stores.

Hybrid search. Combine vector similarity with keyword search. Use SQLite (

sqlite-vec+ FTS5) if you want to stay local with no external dependencies.Accessibility trees over screenshots. For browser automation, parse the accessibility tree. It is cheaper, faster, and more accurate for LLM reasoning.

Heartbeat pattern. For proactive agents, a simple cron + checklist file is enough. You do not need a complex scheduling system.

Authenticate everything. WebSocket, HTTP, local sockets. If it accepts connections, it needs origin validation and authentication. Local-first does not mean security-optional.

Conclusion

OpenClaw is not a framework you adopt — it is an architecture you study.

The project's core insight is that a personal AI agent is fundamentally a gateway problem, not a model problem. Getting the runtime right, queuing, channel normalization, memory, extensibility — matters more than which LLM you use.

The Lane Queue and Skills system are the two patterns with the broadest applicability. If you take nothing else from this article, implement per-session serial execution and consider markdown-based extensibility for your agents.

The security story is equally important. Agent systems have a larger attack surface than traditional applications because they accept natural language input from multiple untrusted sources, including their own extension ecosystems. Build with that in mind.

Build agents that are reliable before they are clever. OpenClaw got that part right.

Enjoying content like this? Sign up for Agent Briefings, where I share insights and news on building and scaling AI agents.

Resources

- OpenClaw GitHub Repository: Source code and documentation

- OpenClaw Official Documentation: Architecture guides and API reference

- OpenClaw Official Website: Project overview and getting started

- CVE-2026-25253 Details: Full vulnerability disclosure

- Agent Skills Specification: The skills format OpenClaw uses at scale

Related Articles

- How to Build and Deploy an Agent Skill from Scratch: Build your own skills using the format OpenClaw adopted

- Don't Let Your AI Agent Forget: Smarter Strategies for Summarizing Message History: Memory management patterns that complement OpenClaw's approach

- Writing Effective Tools for AI Agents: Production Lessons from Anthropic: Tool design principles for the capabilities layer

Agent Briefings

Level up your agent-building skills with weekly deep dives on MCP, prompting, tools, and production patterns.